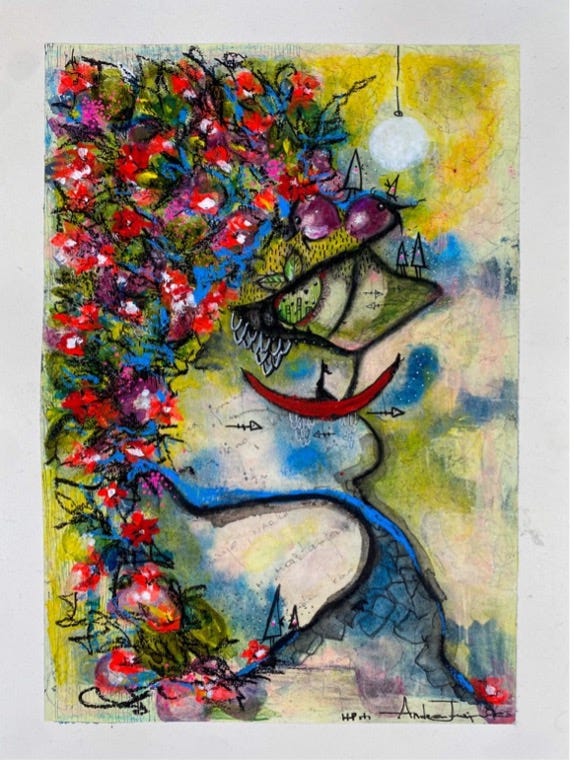

Paintings as Poems

By acclaimed poet, translator, and painter Andrea Jurjević

Hello Friends,

I often wonder how many of us have multiple forms of creative expressions. Maybe some of you write and play the guitar? Perhaps you dance, sculpt, or paint like me, and you use film for inspiration?

To me writing and art go hand in hand. And there are many parallels between them. For example, both poetry and painting require us to slow down and work patiently. Neither lends itself to fast creation (or fast consumption). They both require the use of perception, intelligence, and one’s entire individuality. Both are immensely private practices, and their processes consist of extensive revision and tweaking. And both are based on creating a recognizable artistic voice. It’s fun to reflect on these things, especially given that making time for art often requires a bit of craft in itself.

The last few weeks have been incredibly busy. I’ve been grading finals and designing a summer course that started days after submitting final grades for Spring. As usual, the more demanding my life becomes, the more I start craving writing and painting. So, in the wee hours, I set out working on a painting and returned to an older poem that needed revision. Because of my demanding schedule, the work on these two was slow and fragmented. But that fragmentation made me more aware of my process—I start with a few lines on a piece of paper. I either write or draw them, without much of an idea as to where I’m going with them. The poem I was revising started with a line that’d been on my mind for a couple years: ‘I’m the same age my mother became a widow.’ That’s it. I had a line. I also had a few carbon pencil marks on a piece of watercolor paper.

Both writers and painters start with a blank surface—a piece of paper or a screen. At first that surface is perfectly intact. But the moment we leave a mark on it, we disturb that space. We agitate it and create a problem. We are then compelled to respond to the so-called problem we created by adding more, revealing and experimenting, then subtracting, obscuring, pivoting, trying different approaches until the piece slowly starts revealing itself to us. The artistic process seems to always cycle through creating chaos and inviting order, whether verbally or visually.

But in that interplay of chaos and order, everything hinges on our perception. By perception, I don’t just mean how we as individuals take in our environments, why we notice some details in our everyday lives and miss others, or what it is that makes a person notice a drop of rain clinging to a leaf. I also think of individual ways we perceive and interpret our own work and how we make revision decisions. And this perception can be made clearer.

Everyday perception takes place in fractions of seconds. It’s quick. In a world where we are constantly told to live faster and louder, painting and writing slow us down. Together, they enhance our sense of perception and clarity.

perception(n.)

late 14c., percepcioun, "understanding, a taking cognizance," from Latin perceptionem (nominative perceptio) "perception, apprehension, a taking," noun of action from past-participle stem of percipere "to perceive" (see perceive). Also used in Middle English in the more literal sense of the Latin word. The meaning "intuitive or direct recognition of some innate quality" is from 1827.

—Online Etymology Dictionary

Speaking of perception, a couple years ago I was at a party talking to a watercolor artist with a life-long appreciation for poetry. She said, “Watercolors are like poems, and oil paintings are like novels.” I understood her—there is a delicate, ephemeral nature to poetry. A poem, whether it is lyrical or narrative, is often concerned with things of immaterial nature—feelings, impressions, sensations, perceptions. Poetry’s roots go back to oral culture and music. A poem in that sense is a song. And a song is immaterial.

The comparison to poetry also works in that when we interact with a poem, we can hold the entirety of it in our heads. Unlike a novel, our mind’s eye can apprehend the entire world of a poem. Same happens when we look at a painting.

Perhaps people think that unlike novels, which usually take years to write, individual poems are written quickly. I wish that were the case for me. But the reality is, they tend to emerge slowly. I’m a slow poet who can’t be rushed.

The way I understand the basic difference between prose and poetry is informed by Charles Simic. In his brilliant "Essay on the Prose Poem" he articulates a simple distinguishing characteristic between the two genres: stories create movement, whereas poems resist movement. He says:

Prose poetry is a monster-child of two incompatible impulses, one which wants to tell a story and another, equally powerful, which wants to freeze an image, or a bit of language, for our scrutiny. In prose, sentence follows sentence till they have had their say. Poetry, on the other hand, spins in place. The moment we come to the end of a poem, we want to go back to the beginning and reread it, suspecting more there than meets the eye. Prose poems call on our powers to make imaginative connections between seemingly disconnected fragments of language, as anyone who has ever read one of these little-understood, always original and often unforgettable creations knows. They look like prose and act like poems, because, despite the odds, they make themselves into fly-traps for our imagination.

Ah, fly-trapping imagination!

To me, every piece of art—regardless of the medium or discipline—is simply imagination expressing itself through the artist’s body. We are drawn to art because it makes us slow down and study how imagination manifests itself.

But what to make of that curious statement—“Watercolors are like poems, and oil paintings are like novels”?

Oil is denser than water. It dries more slowly. But can I say that an oil painting tells more of a story than a watercolor? Does a watercolor slow me down more than an oil?

I have made oil paintings before, but I have never written a novel. I cannot fathom creating something that spans hundreds of pages. Personally, I see oil paintings, like watercolors, as writing in paint. They are both like poems. Yet something about that comparison still feels somewhat right.

What about you? Would you say that oil paintings are like novels? I’d love to know.

Love,

Andrea

Love this: "The comparison to poetry also works in that when we interact with a poem, we can hold the entirety of it in our heads. Unlike a novel, our mind’s eye can apprehend the entire world of a poem"--

Maybe for the drying time, the comparison works, as you wrote. But, I do appreciate your logic of comparing a painting, in general, to a poem, much better. Maybe, a novel is more like a long, mural painting I see sometimes on overpass parapets?